Streaming isn't Real

Can we lessen parasocial behavior by acknowledging the art of streaming?

The biggest scandal in Pokémon shiny hunting history was in 2021 when two different streamers encountered a double Starter-Starly shiny almost back to back. This happened the week of Christmas when paid subscriptions and viewership tend to be higher than average due to school closures and “the season of giving” as it were.

That was a lot of words so let me explain: Pokémon means Pocket Monster and they have about a 1 in 4000 chance of having a rare color scheme. Some players, shiny hunters, spend hours and hours hunting these rare variations. In Pokemon’s latest releases at the time, Brilliant Diamond and Shining Pearl, the first shiny players have a chance to encounter is their chosen “Starter” Pokémon as well as the impossible-to-catch Starly they’ll see in the opening tutorial. The odds of both of these Pokémon being shiny at the same time is what statisticians refer to as “impossible for Josh Vasquez to calculate.” Despite the astronomical odds, the indomitable human spirit persevered. Twice. A few days apart.

Huh.

This piece was inspired by this better one by Jake Steinberg on the hyperreality of shiny Pokémon. Please give it a read!

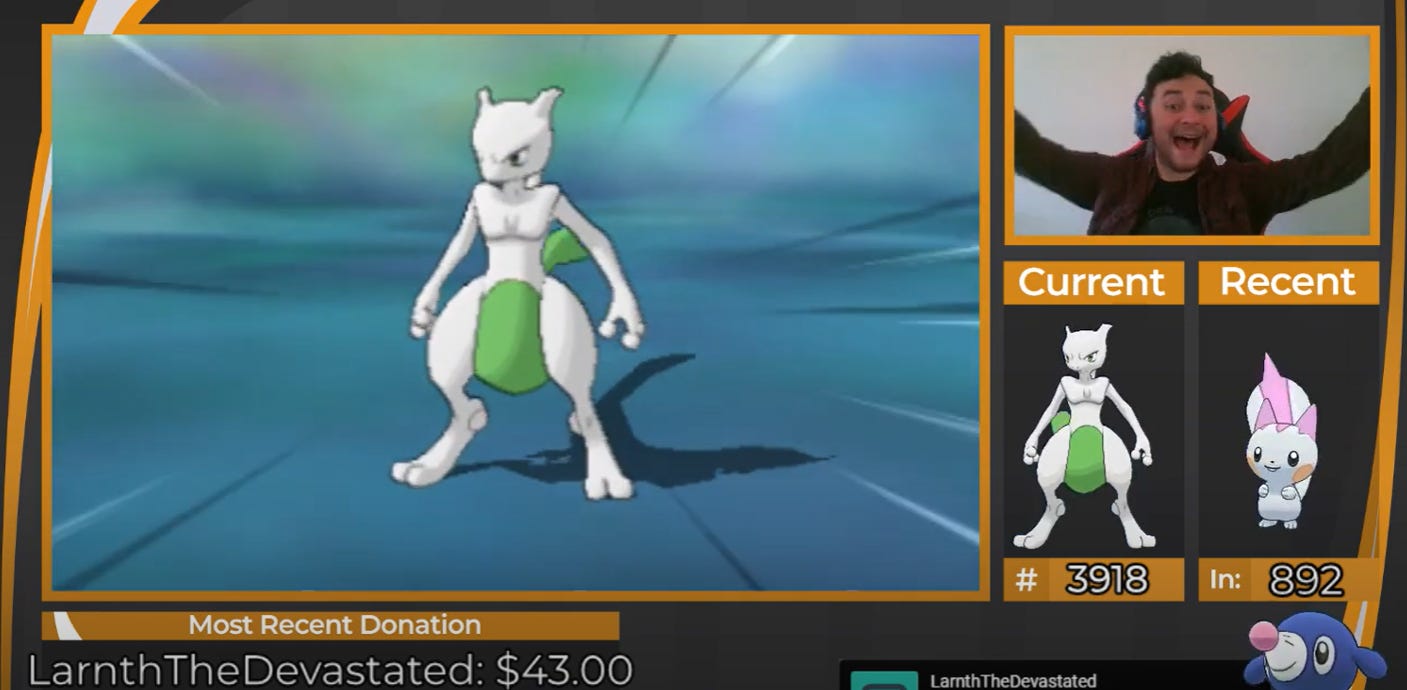

The clips of the reactions to these encounters garnered millions of views and were reported on widely by gaming culture sites. In the second of these instances, the streamer encourages viewers to subscribe because “I’m different.” Less than a week later we would get the apology videos for the faked shiny using a modified Nintendo Switch.

Viewers were upset, feeling duped into believing the streamer’s over the top excitement, and in some cases shelling out $5 for a subscription on Twitch. The shiny, the reactions, the clips, the Tweets were all just a performance orchestrated by the streamers to generate excitement, attract viewers, and gain revenue.

Hey, isn’t that kinda like—

Streamers on Twitch or YouTube can’t be compared one to one to more traditional entertainment, but their promotion and consumption works in similar ways. An actor in a TV show can say something outrageous to generate headlines, a character’s death can light social media aflame, John Cena can turn on Cody Rhodes.

We can “boo” John Cena knowing full well he will be starring as a lovable, funny body guard of some sort a year later because of “kayfabe”— the acceptance of the fictional character and scenario as reality, and conversely, that the reality being presented is a constructed work of fiction. When a shiny hunter on stream exclaims, “NO WAY! LET’S GO!” at a yellow chicken, that’s kayfabe.

Between 2016 and 2019, I was one of these professional shiny hunters. The most excited I ever was about a shiny was my first one ever, a shiny Pikipek live on stream. My heart leapt, and my genuine reaction was stunned silence, another term for a bad clip. As I found more shiny Pokémon I was less and less excited, and my performance grew and grew. The clips got better. I can speak to my experience as a shiny hunter but this performance exists across the streaming medium. See tyler1 dropping a full plate of chicken parmesan, then Hungrybox later dropping an entire pizza. Where these performances can truly fail is in their unoriginality. There is such a thing as bad performance art, after all. The second impossible double shiny didn’t make the first less fake, it just wasn’t exciting anymore, and suspicion arose to make it so. When tyler1 awkwardly presents a plate of chicken in an unnatural way, clumsily tipping it little by little until it falls, its a clever bit of kayfabe— a funny moment to generate a viral clip for his stream. When another streamer follows suit, it is simply a trend within the competitive gamer streaming sub-category.

As audience and streamer, we are all better off acknowledging the kayfabe within the medium. Authenticity has long been the backbone of content marketing, but authenticity need not be absent in performance. Between exciting shiny encounters (which for me happened much less frequently than others in the community of Pokémon streamers), in the slog of seeing Pokémon after Pokémon is where I found the most genuine interaction. This is where I built community, spoke out about my views, had real conversations. This is why it’s important that kayfabe works both ways. It is a shared responsibility to acknowledge the separation between the real and the performed. We can better appreciate streaming as the art it truly is: big, exciting, sometimes calculated moments strung together by a shared communal experience.

My wife, whom I may not know if not for my time as a professional shiny hunter, will sometimes call me out. “You said that in your streamer voice,” she’ll say at the dinner table. Perhaps it was a habit I developed. Something I put on to generate the thing that would attract the most praise. In streaming, this is simply how the game is played and the excitement generated, even if predetermined, is real. By acknowledging the kayfabe in streaming, we can better enjoy the art, and streamers can better creatively express themselves through their performance, hopefully with less fear of the worst tendencies of parasocial viewers. That is the future of streaming I look forward to. More over the top, hilarious, heartfelt, inspiring moments understood as the performances they are.

At the end of my time streaming, what I have left are the clips, each an exaggerated persona to punctuate the end of a long shiny hunt, but still dear memories. Performing on stream, writing a newsletter, or any other creative endeavors I may have had each convey a fiction, a morphed version of life as it truly is but with real pieces of myself sewn in. I put on the streamer voice less and less, separating myself from the streamer I once played, but the persona lives in the clips made along the way, and the memories attached to them.

I read this article in a 'streamer voice' and now I don't know what to believe any more.