The following contains spoilers for all of Clair Obscur: Expedition 33.

“I found myself coming down here more and more. Such a lovely smell from the dryer sheets. I like it because there is a window that is always opened a little crack there… It felt just like her to lead me to a place where I would experience something new and special.” -Marcel the Shell with Shoes On

On Avoiding My Chores

I'm a podcast enjoyer. My favorite chores podcast is Search Engine, the investigative reporting podcast built on the vestiges of Reply All. In an episode from last year, PJ, the host, talked to people about their thoughts and experiences with an emerging business that would train an AI chatbot on the speech patterns and personality of a deceased loved one that you could talk to forever. Of the many opinions expressed on the episode, one stuck with me. To paraphrase, when we refuse to grieve, to deny the reality, it takes away the opportunity to feel their memories as their presence. We can't feel their presence in the wind, or in the smell of a favorite homemade dish without accepting that that is where they are now. A hummingbird became the symbol of my grandpa after he passed. He would sit in his recliner chair with a perfect line of sight to the front porch where a feeder hung and he'd watch them, content to ignore the TV just behind him. An ornament of a hummingbird hangs next to his picture on the ofrenda in my mom's house.

I listen to Search Engine every week while doing the dishes and for the past 6 months I've ignored an empty bowl, "QUEEN" etched into its side with a couple small remnants of crusted cat food at the bottom. At first, my wife and I were aware of our avoidance. Our cat, Tink, had her own room in our house that we knew we had to start using again or else risk being too afraid to ever go back in. The more subtle means of avoidance were easily explained away as procrastination. I'll get to that bowl eventually, it's not like anyone's using it. The honest truth is it feels like the last piece of her I have.

“…that is the relentless presence of death. Not only is it inevitable in Clair Obscur's world, but it is predetermined and tangible. It stares at the people of Lumiere from a monolith any time they dare to lift their heads up.”

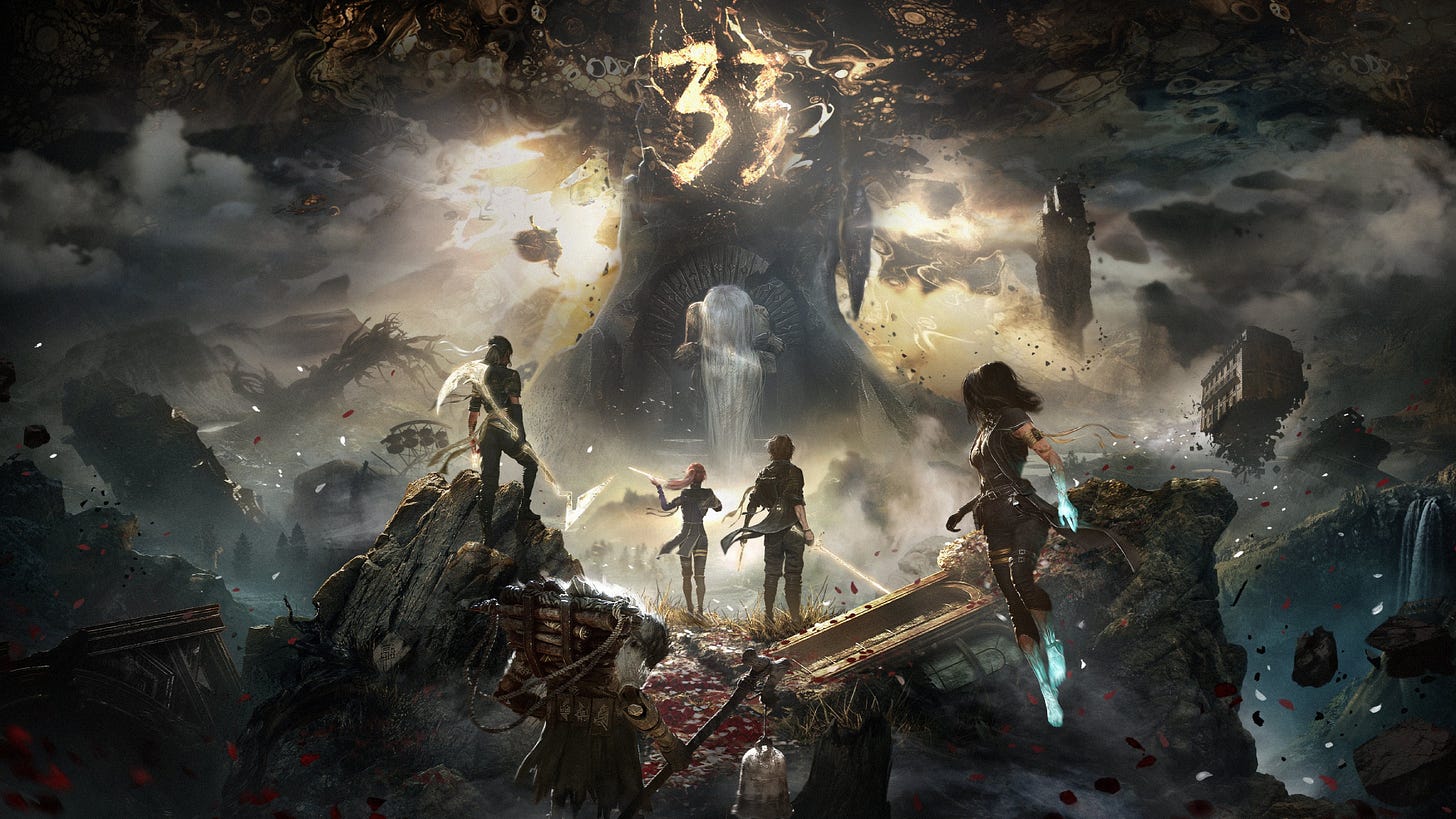

What does any of this have to do with 2025's surprise hit RPG, Clair Obscur: Expedition 33? The game takes place in a warped version of our world in which a merciless god, The Paintress, paints a number each year on a monolith, instantly erasing anyone that age and older from existence. Each year the number decreases. It imagines a world plagued by death and hopelessness for the future, their only hope being a yearly expedition of their oldest citizens. Their last year is spent in the pursuit of hope for the future by killing The Paintress. Even in their efforts, there is a doomed overture. "For those who come after" is the moniker, their greatest hope is to die to make the next expedition easier. Does anyone dare imagine they will reach the monolith and kill the Paintress?

Expedition 33 is made up of many 32 years olds, and one 16 year old with no real family. Maelle has already seen everyone she knew die, and hates the Paintress even more than most. Her brother figure, Gustave, a clever, overworked magician, Lune, and Sciel, the fierce fighter who lost her husband and child, make up the remains of Expedition 33 after their entire crew is attacked immediately upon landing on the continent outside their borders. They desperately try to recollect themselves and continue the mission after a devastating loss, and with the help of a mysterious and haunting figure, The Curator, they get back on track to hunt The Paintress.

The world is in a constant state of grief and fear. They know their fates; it looms over them from afar, its shadow casting despair to the far reaches of the world. Some have grown to hate the Expeditioners, accepting what is rather than the constant struggle to change what they believe cannot be changed. There is peace for them in that acceptance. It would, after all, give them another year to be with the ones they love instead of heading out on the Expedition just to die. Those left behind by Expeditioners are either proud that their loved one made a heroic sacrifice, or resentful that they chose the Expedition over time with them. It is important to remember, no one in Lumiere, where they live, has any idea of the progress or even possibility of reaching The Paintress, as no expeditioner has ever come back. The Expedition is entirely a leap of faith even over 100 years since The Paintress appeared.

When Expedition 33 is attacked upon their arrival on the Continent, Gustave observes the piles and piles of mangled corpses from past Expeditions- it would appear, especially in his frantic state, that no Expedition in all of this age has ever made it past the beach. Hopelessness, ever present in the age of The Paintress, overwhelms Gustave as he places his gun to his head. Sat up against a tower of the bodies of Expeditioners past, Lune finds him just in time.

Lune, logical and by-the-book to a fault, comforts him the best way she knows how. "For those who come after," "When one falls, we continue," all of the monikers of the Expedition are rooted in in the same hopelessness in which they live their lives. Bad things will happen, we've accounted for this, we move on.

Hope and/or hopelessness, then are our central themes in my estimation heading into the first act of Clair Obscur. The feeling is well established in the text and tonally within the dark lighting and music. The attack at the beach shifts between black and white and gory splashes of red. The tone is not frantic, but somber, as if this was the only way things could have gone. Like Lune reassures Gustave: we've accounted for this, we knew this, we continue. Hopeless is their home. Suicide is alluded to on multiple occasions, and after Lune saves Gustave, he confides in Sciel who he knows attempted suicide herself after the loss of her husband and child. She, like Gustave, found a reason to go on, even if there are those who would believe the Expedition is a form of suicide in the end. There is hope in their fight, even if only as a faint light at the end of a long and impossibly dark tunnel. I can picture and feel the kind of hope the Expeditioners have, a hope that they can't even believe in like an accepted lie you tell yourself to keep going.

Why does Gustave go on then? Presumably he was ready to die from the start, and when all truly seemed lost, he proved that. After he is saved, Gustave will prove his willingness to die again at the end of act one. He is confronted again by the old man on the beach, Renoir. The man who massacred his expedition. Combat ensues, and we are forced to levy futile attack commands against him. Hopeless. Hopeless if not for his belief and love for the family he chose to take in: Maelle, his most trusted confidant, a sister, friend to him. She is there behind him, watching helplessly, and she has to live. All he can do is fight, even if it is meaningless, so that she might live.

Enter Verso. Renoir and Verso were part of the very first expedition, Expedition 00 and have managed to live all this time despite the Paintress' cruel canvas. How? And why does Maelle see the dreaded old man and a strange girl in her dreams? Slowly we learn through act two of Verso and Renoir's relationship as father and son and the girl who was burned in a fire during the fracture that brought about this world. Renoir was granted immortality by the Paintress, as was Verso, and Renoir is keen to keep things as they are. Verso is done with the cruelty and pain it's caused, and has helped countless other Expeditions in their attempts, but none to any avail. Verso is determined to finish what he started with that first expedition, and in the process has seen all of his companions, year after year, die.

Two more themes spring to mind. One has been sutured tight to our previous theme of hopelessness, and that is the relentless presence of death. Not only is it inevitable in Clair Obscur's world, but it is predetermined and tangible. It stares at the people of Lumiere from a monolith any time they dare to lift their heads up. The grief stricken residents carry that feeling day after day, their sense of family shattered. Parents will die young, couples grapple with bringing children into a world with no future, everyone must decide between a year with their loved ones or joining the Expedition. Nothing is easy. Familial bonds lace through the woven narrative, tying every choice, twist, and turn together. From Maelle's life as an orphan bouncing from home to home, Sciel's loss of her husband, Lune being trained since childhood for the Expedition, and Verso who would oppose his own father for what he believes is right, these dynamics take shape slowly, subtly until they engulf each character. Suddenly Lune's staunch dedication to the Expedition becomes a way to honor her family who she holds some resentment towards for forcing her into the only worldview she knows. Sciel decided long ago what she must do, as her hope was to one day see her family again. Maelle would accompany Gustave, the last family she ever had.

When the act three twist arrived, I was not surprised. Not in a braggadocious, I-am-so-smart way. That people are dying in a hopeless world was not, to me, the biggest idea this game had. In fact, I see that pretty often. Clair Obscur has packaged that idea in a unique and interesting way that deserves tremendous praise, but that is simply the hook. The question is why?

The characters in Expedition 33 are a fiction within a fiction. The Paintress is a god in this world in the same way a writer is the god of their story. The Paintress is the reflection of the real person, Aline, who's son, Verso died in a fire saving his sister, Alicia. The Verso we know, and the Maelle we know are the versions of those two siblings inside of the painting. Renoir is also the painted version of the real Renoir, their father and Aline's husband. The painted version of Renoir was created by Aline to protect her so she would never be forced to leave the painting where her son was still alive. The real Renoir and Alicia (Maelle), went into the painting to bring Aline back. So why is this fictional Verso who has no real life counterpart so determined to destroy the Paintress and help the Expeditions? There are a number of reasons, the main being he was not created by Aline. The entire world was originally painted by Verso before he died. Aline became consumed by it and fled to it to keep a part of him alive. Verso holds the memories of his creator still and knows it is best for his mother to leave the painting. If that was a lot, the world we've ventured through is the creation of a family of artists who are, in different ways, grieving the death of a son and brother.

Maelle regains her memories as Alicia and we find that not much has changed. She has a family which has been torn apart by tragedy. She holds tremendous sorrow in her heart as she believes it is her fault Verso died in the fire. He died saving her, just like Gustave. The artwork that is the world of Lumiere-- the Expeditions, the creatures they meet, the titanic Axions, and The Paintress-- is a collaboration among a grieving family, the basis for which was crafted by their lost loved one. For those who come after, we continue. That anyone would be lucky enough to have something as true of someone as a piece of art they've created is the most precious gift I can imagine. Maelle, Alicia, honors that by completing Verso's wish, crafting the story with her as the hero, and him by her side, supporting her every step of the way. He loved her in such a way that he would give his life so hers could continue, even if when he stepped into the fire that was never a guarantee. Like the Expeditioners he created, the smallest glimmer of hope was all he needed, the tiny flicker of light at the end of the impossible dark. That she might live.

Now, however, Verso is trapped. The painted Verso is a prisoner in the painting, kept alive as a hollow copy by his grieving mother who just wants him to be there with her. This Verso isn't making a sacrifice by urging his mother and Maelle out of the painting. This Verso wants to be free. When all is said and done the player has the choice: help Verso defeat Maelle, the painted version of his sister, so that she can awaken to live her true life, or choose Maelle and let her live out the fantasy with her brother, forever living in the painting where they are together while her family outside watches her body waste away.

I chose Maelle. I had seen Clair Obscur as her story even when we play as Gustav in the beginning, and I thought it right to give her the agency in the end. She successfully traps Verso there, repaints all of her friends, and we flash forward to a future where they all grow old. The expeditioners sit in a packed theater to watch Verso perform on his piano. Sorrow stains his face as he sits there, and from his perspective we see him try to resist playing. But as merely a painting, a false memory, he is beholden to Maelle's will, her own cursed face flashing before him, forcing his hands.

The other ending, in which Verso forces Maelle out of the painting and into the real world, ends on a somber, but hopeful note. Her family grieves together at a memorial and Maelle is able to have her own version of the hummingbirds that remind my family of my grandpa. She holds a stuffed doll made in the image of one of Verso's creations, the lovable Esquie, and she sees for the final time the images of her lost friends and brothers wave goodbye and fade away; always there when the wind blows just right.

In playing Clair Obscur Expedition 33, and subsequently writing this reflection, I cried several times, each time about my cat, Tink. I didn't expect that the opening moments in which Gustave says goodbye to his girlfriend, Sophie, The Paintress' latest victim, would effect me so. I woke up early to play before work having heard how spectacular the game was and before I could clock in, I was in tears. On the day last December when Tink passed, I was home working. She had been sick and wasn't eating, so we knew it wouldn't be long. My dog started barking upstairs. I'll never forget he was the one who alerted me to what was happening so I could be there. I sat on the floor with her, and pet her, and I told her, "I'm here," over and over.

These are the last words Gustave says to Sophie as she is spirited away.

If the game had ended up being a fun romp through an exciting new fantasy world, or any old run-of-the-mill RPG, I would have still had that moment. It was special from the opening hours. What it turned out to be was a true work of art, a masterclass on all fronts in the multidisciplinary medium of video games, and more than anything else it gave me actionable inspiration that helped me in my real life. Tink's food bowl was the hardest dish I ever had to wash in a world of dirty dishes I hate washing, but doing so made room for her memory and our love for her to live on.

Finally got around to commenting!

Really nice piece! And thanks for sharing. It can be really hard to pour your heart out on the page like that.

Did you watch the Verso ending? I'm polling my friends, and I think I'm the only one among them who chose it.

Amazing article! The added personal experience was a nice touch.